A False History

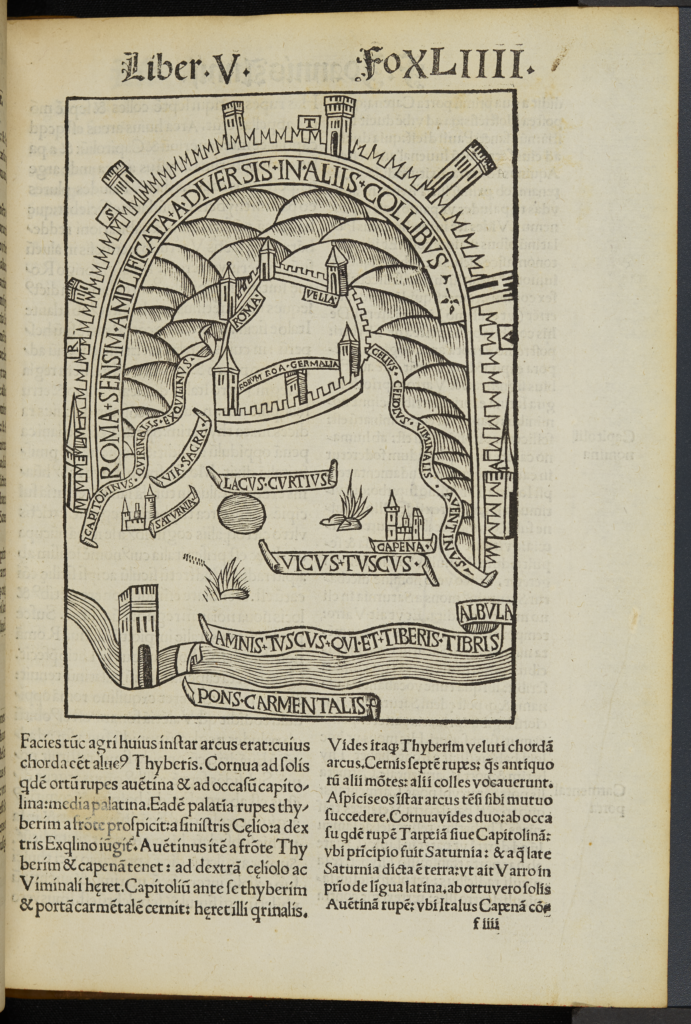

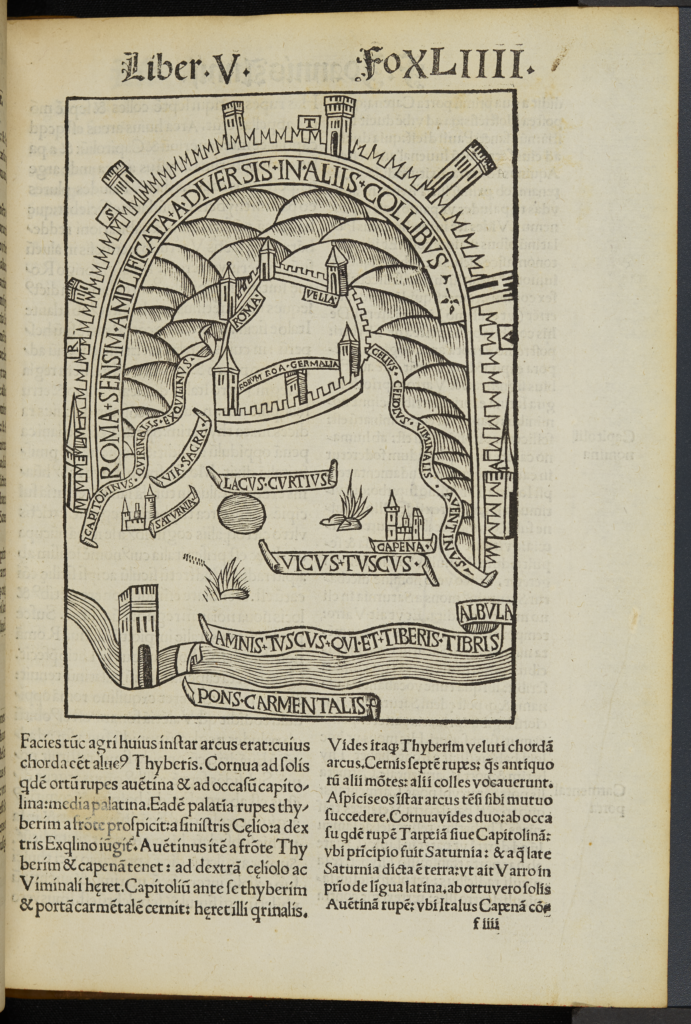

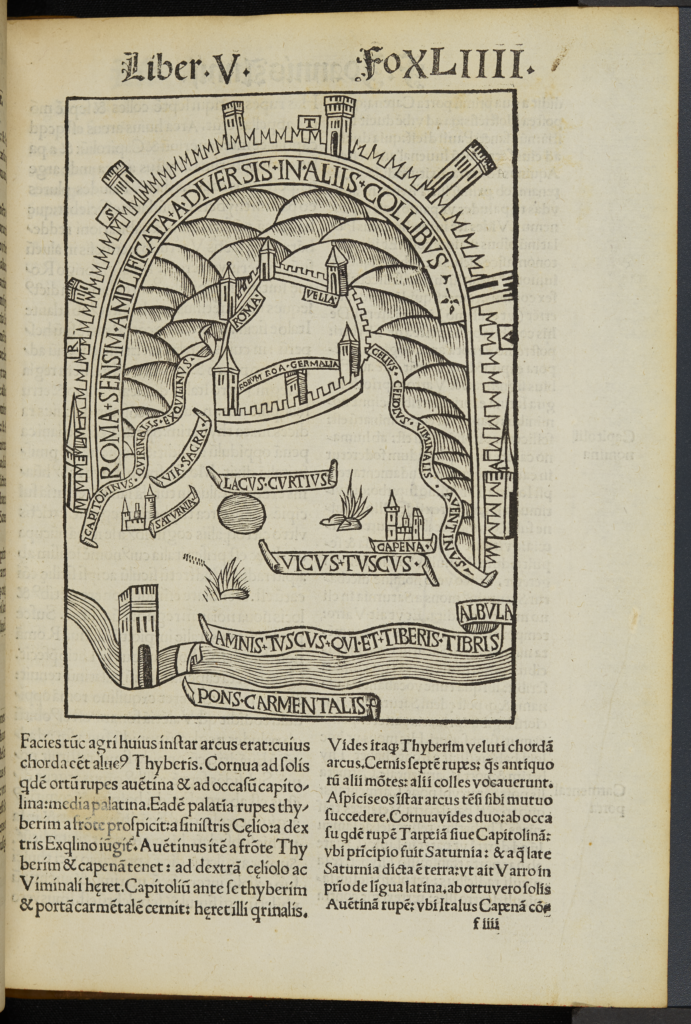

Annius of Viterbo (Giovanni Nanni, 1437-1502) was a Dominican Friar held in some regard during his lifetime but remembered now as a prolific and successful trickster. Although his frauds were many, various, and in some cases highly elaborate — he once staged an archaeological dig in which he unearthed, to the astonishment of observers, a fantastical array of mythological statuary, every piece of which had been prepositioned for dramatic effect — the Antiquitatum variarum is perhaps the most important. The book contains what is claimed to be a series of insightful and surprising fragmentary texts from Greek and Latin authors, discovered in Mantua. Much of what is included is quite convincing and almost of all of it is quite compelling, but not one piece of it is actually authentic.

Magdalen College Library, C.1.5. Annius of Viterbo (1512). Antiquitatum variarum (Commentaria super opera diversorum auctorum de antiquitatibus loquentium) volumina XVII. Paris: Printed by Josse Badius for Jean Petit.

A Hidden Author

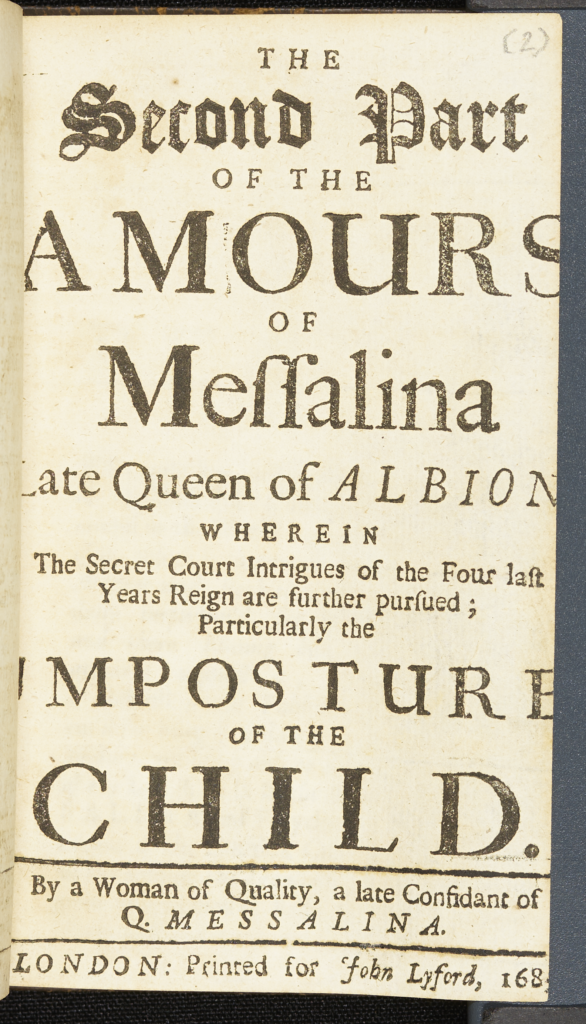

This book is an interesting example of a form of “false copy”. The English text is put forward as a translation of a French volume of the same name which itself claims to be a translation from the English. Valeria Messalina (20-48 AD), the third and penultimate wife of the Roman Emperor Claudius, is interesting not just as an historical individual, but also on account of how her legacy — real or imagined — has passed into myth. Messalina’s life is recorded as a colourful one. She is said to have taken many lovers before eventually being executed for plotting against her husband. It is impossible to know whether she was as promiscuous or outrageous as the historical record claims, or accounts of her character were embellished to justify her execution. Whatever the truth, her name has come to symbolize feminine sexual appetite and liberation. In print, she has been approached over the centuries with a form of guilty curiosity. This book is the physical embodiment of the tension between sexual fascination and the moral weakness this fascination might be perceived to expose: to write such a book would raise awkward questions, but to translate it from French, far fewer.

Magdalen College Library, a.1.19(2). Woman of Quality (1689). The second part of the amours of the Messalina late Queen of Albion. London: Printed for John Lyford.

A Spurious Foreword

Widely regarded as the father of the heliocentric model of the solar system, this work of Nicolaus Copernicus (1473-1543) — a giant of the Polish Renaissance —ultimately overturned the Ptolemaic, geocentric view of the heavens that had persisted since the first century AD.

Copernicus completed the manuscript of De Revolutionibus only shortly before he died. As a result of this, and the hands it passed through prior to publication, there was for a long time controversy over what constituted the “authentic” version of the text. An anonymous foreword appears in the book addressed ad lectorem de hypothesibus huius operis (“to the reader concerning the hypotheses in this book”). This short introduction guides the reader’s interpretation of the text, encouraging us to understand what is put forward as a mathematical model to explain the practical observations of the astronomer rather than literal truth. This suggestion is perplexing given the highly prescriptive nature of the rest of the book, and suspicions around authorship were confirmed when a copy of the original manuscript, retained by Copernicus (who perhaps anticipated trouble), was rediscovered in the eighteenth century. The foreword has since been established to be an insertion by the Lutheran preacher Andreas Osiander. There has been much discussion about Osiander’s motivations. Many consider him a traitor to scientific method and his actions to be no more than a brazen attempt to frustrate the acceptance of Copernicus’s model. There are those, however, who suggest that his aim may have been, at least in part, to cushion the impact of — and therefore stimulate constructive discussion around — this highly contentious set of new ideas.

Magdalen College Library, Q.10.11. Copernicus, N. (1543). De Revolutionibus Orbium Coelestium. Nuremberg: Printed by Johannes Petrejus.

A Partially Plagiarised Text (and the Art it Inspired)

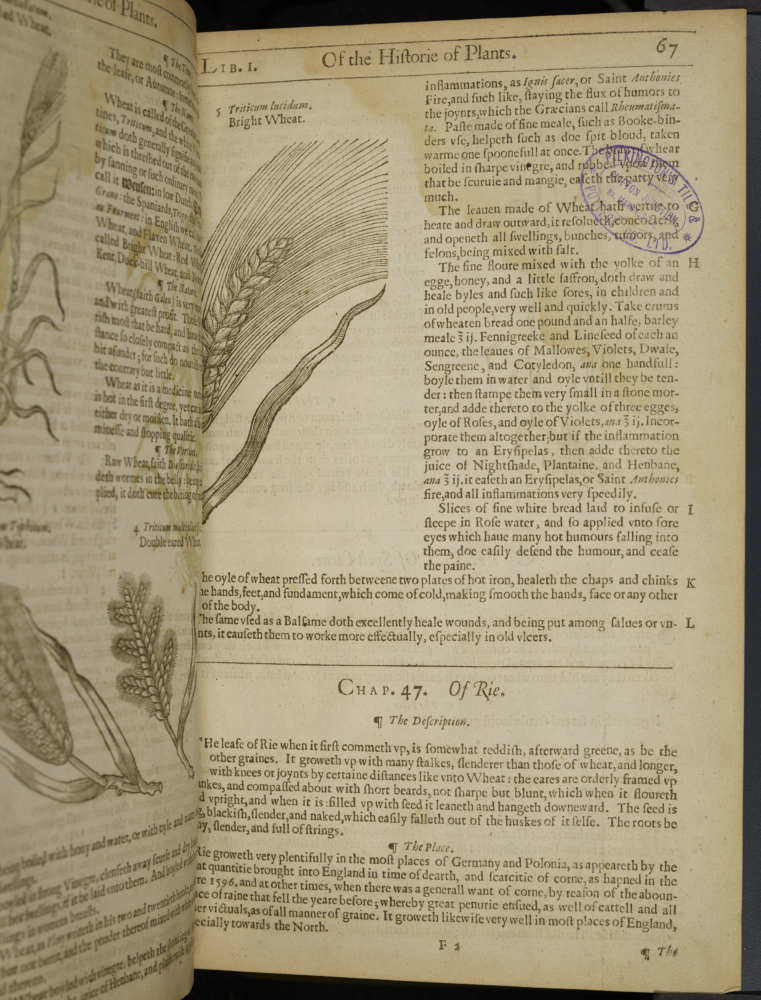

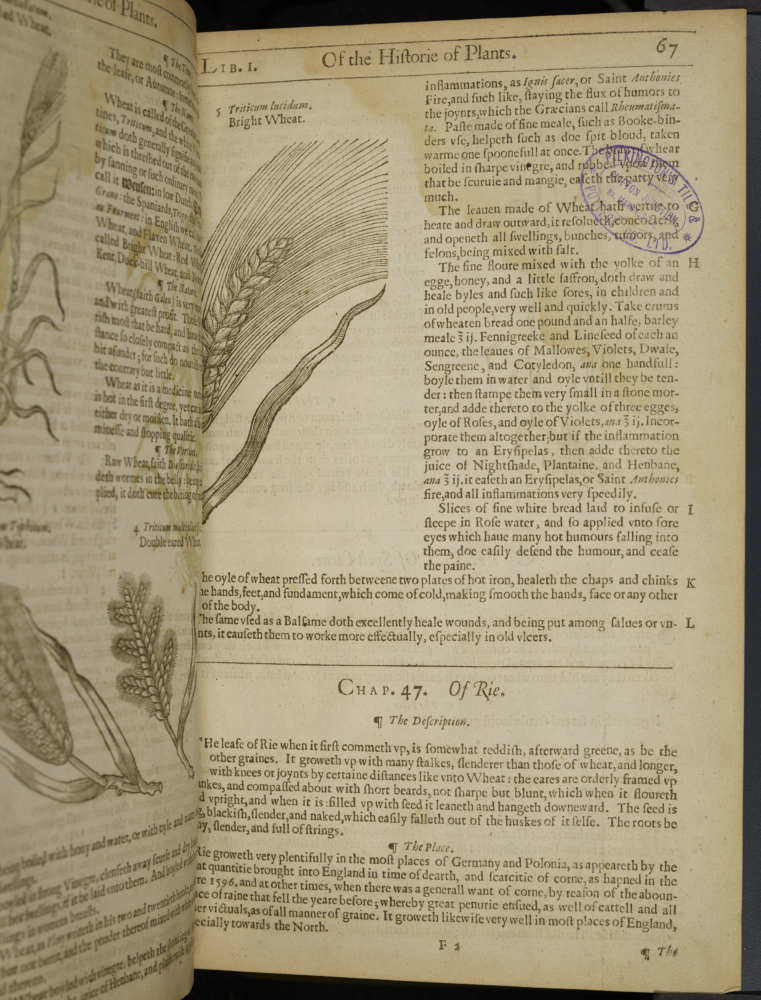

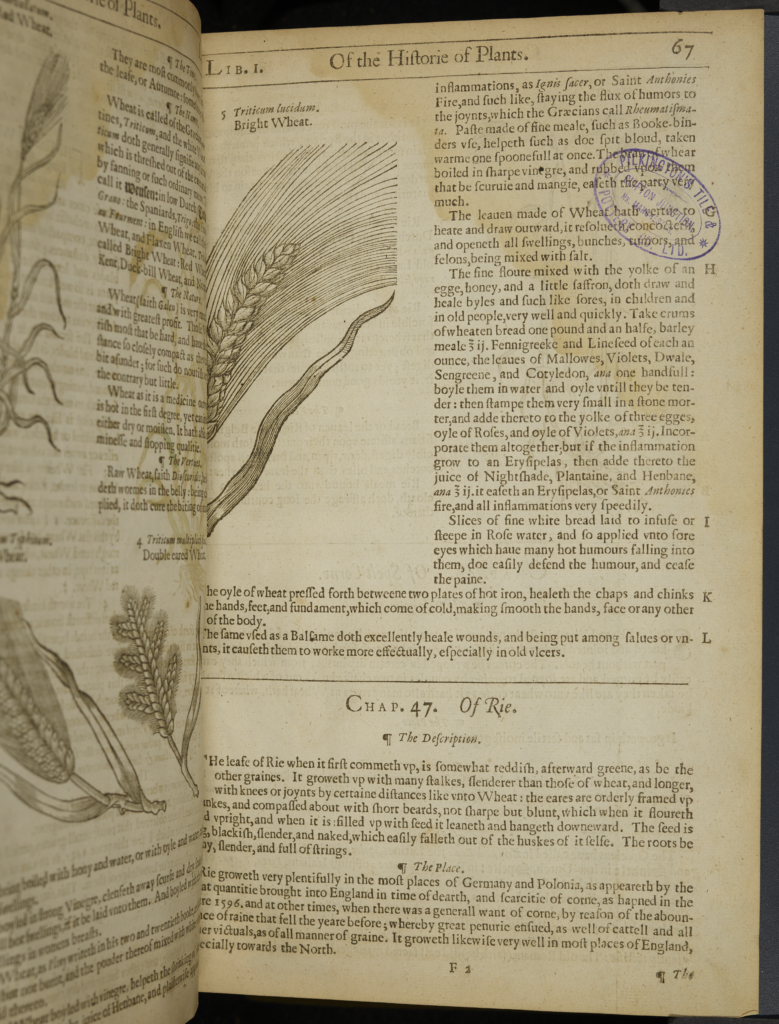

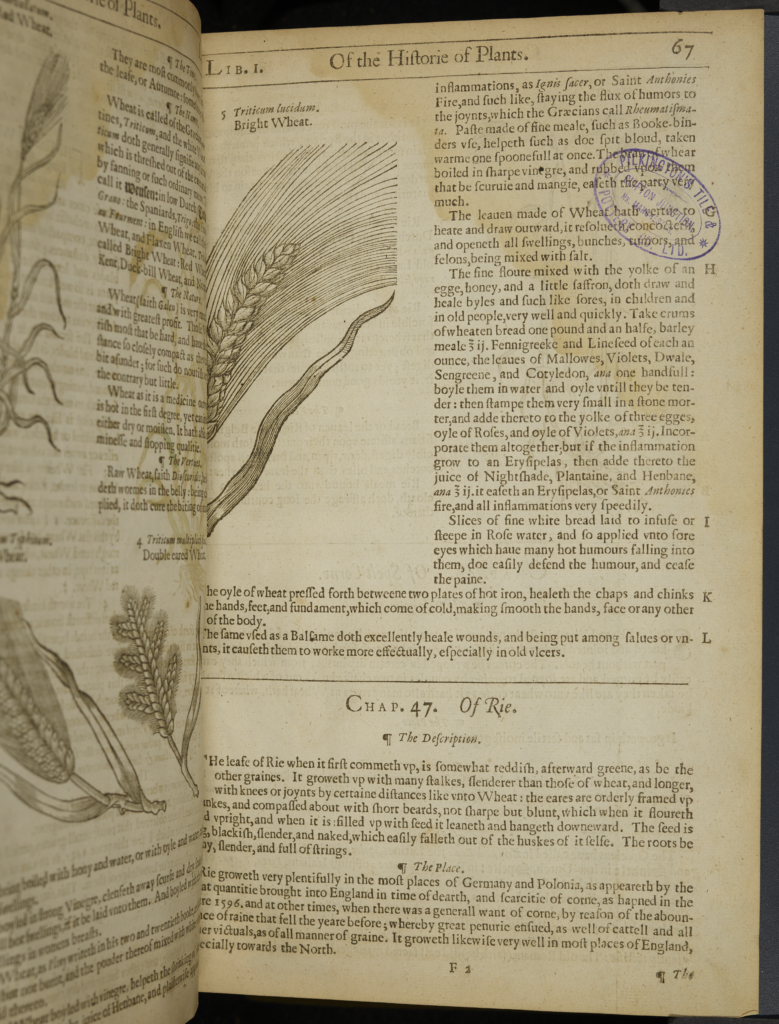

First published in 1597 and still in print, The Herball, or Generall Historie of Plantes, is a monumental work by John Gerarde (1545-1612), commonly known as “Gerarde’s Herball”. The book was for many years considered the standard botanical reference text and — on account of the woodcut illustrations it contains— continued to have influence as a stylebook well into the twentieth century.

Gerarde was a practical man rather than an academic— an herbalist and horticulturist — who maintained a substantial garden at Holborn as well as overseeing those of several notable estates. Gerarde’s Herball began as a project to translate a popular Latin herbal, Stirpium historiae pemptades sex sive libri XXX (1583), into English. This book was itself a translation of an earlier volume published in Flemish some thirty years previously. Though Gerarde completed the text, the undertaking was begun by Dr Robert Priest, a scholarly man who died prematurely in 1596. Gerarde would later be criticised for not sufficiently acknowledging Priest’s contribution to the text, which — through what is known about the overlap between Priest’s research and the contents of the volume — appears to have been significant. The 1,800 woodcut illustrations that it contains were not all purpose-made, but overwhelmingly recycled from a series of sixteenth-century botanical books from which it appears Gerarde also gathered text — a state of affairs that led to yet further allegations of plagiarism. Perhaps unfairly, some of the best-known facts about the book concern the mistakes within it. In particular, it is credited with the first English-language description of the potato but claims that the plant originates from Virginia in North America, and — though generally sober —it famously includes an illustration of a “barnacle tree” that “bares geese”. Despite these foibles — and perhaps latterly, because of them — the book was enormously influential and, with each passing century, grows to be more beloved by book collectors and botanists alike. This copy, dating from 1636, was previously in the library of Pilkington’s Tile and Pottery Company, where it provided inspiration for a wide range of botanically themed ceramics.

These items were loaned to us for the physical exhibition by the Institute for Digital Archaeology. Gerarde, J. (1636). The Herball, or Generall Historie of Plantes, London: Printed by Adam Islip Joice Norton and Richard Whitakers. Ceramic tiles from Pilkington’s Tile and Pottery Company, inspired by Gerarde’s Herball.

A Facsimile

William Gilbert of Colchester (1544-1603) was educated in medicine at Cambridge and elected President of the Royal College of Physicians in 1600. In 1601, he became physician to Elizabeth I and was retained by James I when she passed away in 1603.

Exactly how Gilbert found his way from medicine to magnetism is not clear but if it was by accident, it was certainly fortuitous. His De Magnete, published in 1600, is widely accepted to be the first text to introduce the idea of the Earth originating its own magnetic field. As remarkable, though, as this new insight, is the way that it is presented to the reader. The greater part of De Magnete is given over to detailed reports of extensive experiments that Gilbert conducted to support his theory of terrestrial magnetism and — produced at a time when physical science was a largely derivative and theoretical enterprise — the book is generally considered to be the first within the modern Western scientific cannon to advocate for an experimental approach to the study of the natural world.

This facsimile English translation edition of De Magnete, printed by Chiswick Press, is an excellent example of high-quality, turn of the twentieth century, letterpress print-work. The book was produced through a subscription society, The Gilbert Club, founded by the eminent Quaker physicist and electrical engineer Silvanus Thompson (1851-1916) in 1889. Announcements relating to the inaugural meeting of the Club record a preliminary list of a little over 30 members — among them, Lord Kelvin, Lord Rayleigh, John Lubbock (the first Baron Avebury, of the famous 1860 Oxford evolution debate), Sir Oliver Lodge (the radio pioneer), the great civil engineer Sir Frederick Bramwell, John Henry Poynting (of the eponymous vector), Dewar (the inventor of the vacuum flask), and the pioneering neurosurgeon Victor Horsely.

This star-studded and varied group is reflective of the fact that the Gilbert Club’s goal was not just to do good service to its namesake’s legacy. It was also about kinship in a time of scientific turmoil. The last decade of the nineteenth century was one that ushered in a period of transition; when science shifted from a philosophical pursuit that considered its chief responsibility the intellectual betterment of mankind, to an enterprise that underpinned industry and commerce in new and disruptive ways. The production of this “copy” provided a forum for the leading lights in then nascent fields of technology to debate the controversies of the day under the mediating influence of a shared endeavour.

This item was loaned to us for the physical exhibition by the curator, Dr Alexy Karenowska. Gilbert, W. (1900). De Magnete, Magneticisque Corporibus, et de Magno Magnete Tellure: On the Magnet, Magnetic Bodies also, and on the Great Magnet the Earth, London: Chiswick Press. Translated by Silvanus Thompson.