A Defence of Historical Accuracy

Michael Faraday (1791-1867) was one of the most important and successful physicists and chemists of his generation — in the words of Ernest Rutherford “one of the greatest scientific discoverers of all time”. As a young man, he received almost no formal education but gained access to an extensive range of contemporary scientific and philosophical texts through his apprenticeship to a local bookbinder.

As an eminent, well-known, and well-respected scientist, Faraday was much sought after to lend his expertise or reputational weight to a wide range of committees, commissions, and societies. One such committee was that formed to examine the question of the original colour of the Elgin Marbles — the Parthenon sculptures housed in the British Museum. The question of polychromy in ancient Greek art was, at the time, a vexed one. With the beginning of the nineteenth century came a fresh enthusiasm for Ancient Greek and Roman art. The preferred aesthetic of the neoclassical period, however, was not so much aligned with ancient taste as it was with its residue. By the 1830s it was well-known, but not well-accepted, that Greek statuary was commonly painted — likely, in garish colours. This technicolour reality sat uncomfortably against the shining white marble of British Establishment Neoclassicism.

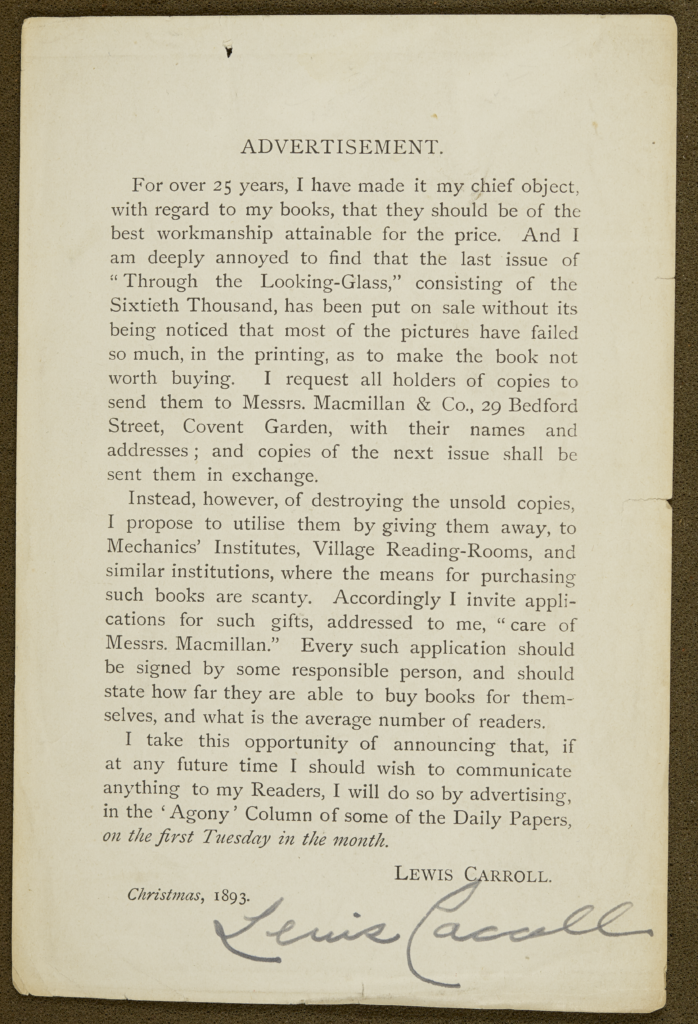

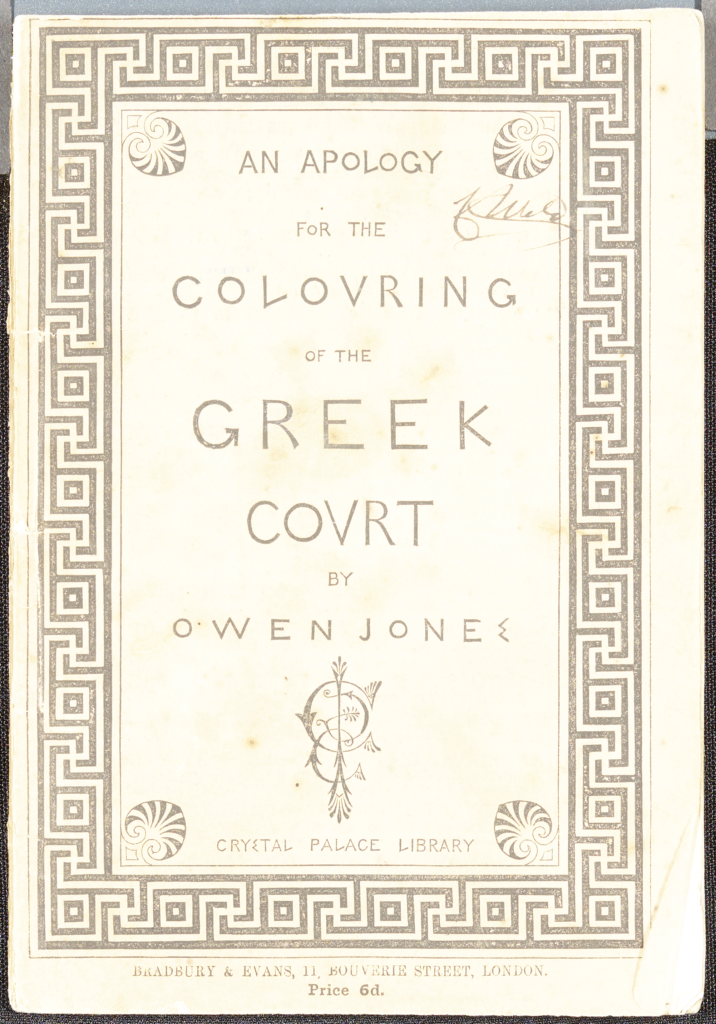

Published in 1854, An Apology for the colouring of the Greek Court was written by the influential architect and colour theorist, Owen Jones (1809-1874). Jones was commissioned to design the Fine Arts Courts of the Crystal Palace of Sydenham — a spin-off of the 1851 Great Exhibition. In considering the colouring of the Greek Court, Jones undertook extensive research and formed his own views of what constituted an “authentic” vision of antiquity. This pamphlet explores Jones’s decision-making process and exposes the extent to which the evidence of Faraday — encumbered in his investigations by the extensive scrubbing and acid-washing to which the sculptures he was commissioned to examine had been exposed — was abused by the 1936 committee.

This item was loaned to us for the physical exhibition by the curator, Dr Alexy Karenowska. Jones, O. (1854). An Apology for the Colouring of the Greek Court. London: Crystal Palace Library and Bradbury & Evans.

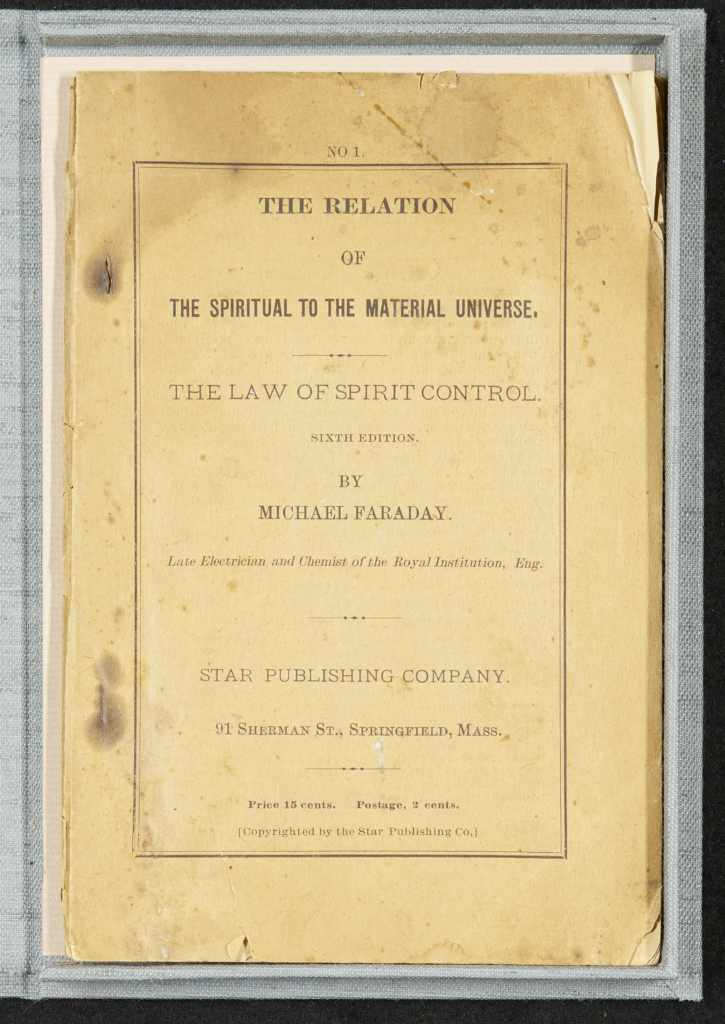

A Mystery Author

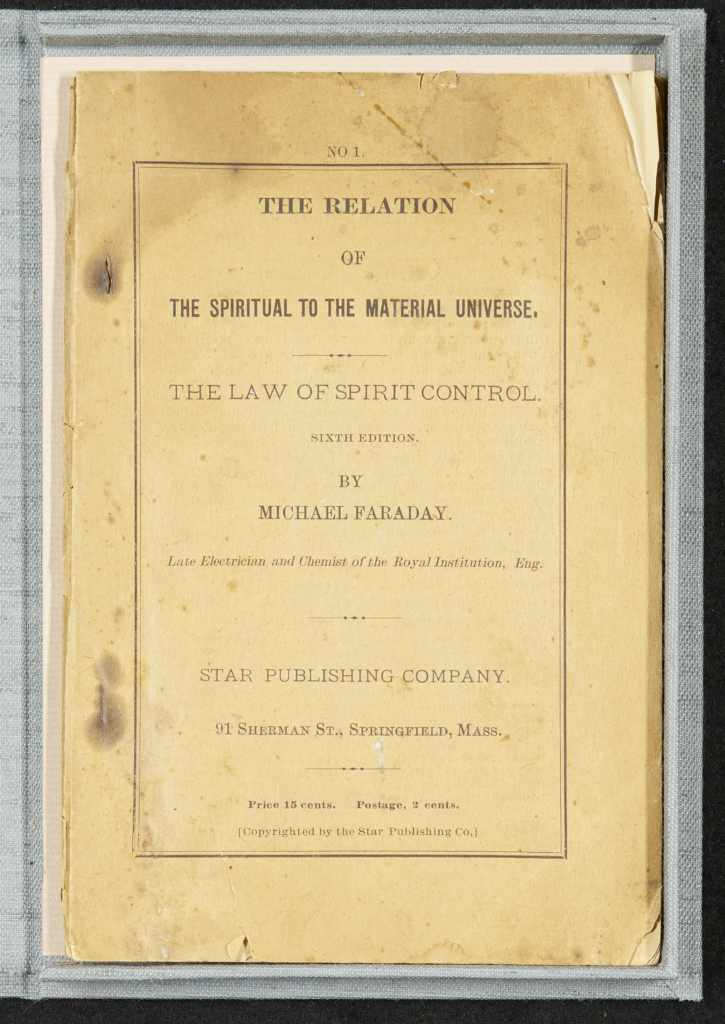

Published in Boston, Massachusetts, this little publication contains a series of representations in support of the practicality of communication with the spirit world, allegedly endorsed by Michael Faraday. It is likely, though not certain, that the association with Faraday is a fabrication — an attempt to lend authority and respectability to the contents by associating it with the famous scientist. Strengthening this theory and yet also opening a door to an alternative interpretation, is the fact that Faraday, alongside other notable contemporaries — including Oliver Lodge, Lord Rayleigh, William Crookes and Joseph Thomson — took an active interest in the emerging cult of spiritualism. In 1853, Faraday undertook an investigation into the origin of two then much-discussed “spiritualistic phenomena”, those of levitation and turning tables, proving to his own satisfaction, and to that of a significant audience, that these effects had earthly explanations.

On account of their flimsy and inexpensive construction, publications such as these typically survive poorly, if at all. As a result, and perhaps ironically, they are now prized by collectors for their rarity and the glimpse they give into otherwise ephemeral aspects of nineteenth-century society.

This item was loaned to us for the physical exhibition by the curator, Dr Alexy Karenowska. Unknown author (1850s). The relation of the spiritual to the material universe: the law of spirit control. Springfield, Massachusetts: Star Publishing Company.

A Pirate Edition

A pirate edition of a book is an unauthorised copy. Commonly produced contemporaneously with the authentic text, pirate editions were created by enterprising printers who saw an opportunity to cash in, generally in one of three ways — by replicating a sought-after text whose print-run failed to meet popular demand; by offering a desirable publication at a lower price-point; or by producing “black-market” copies of books that had been withheld from sale or banned by censors. In the case of popular authors, considerable efforts were made to discover and destroy pirate texts and, as a consequence, pirate first editions of many notable publications are now considerably rarer and more valuable than the “real thing”.

This is a beautiful — if inexpensively produced — pirate copy of the first English edition of Oscar Wilde’s short tragic play, Salome. The play was originally published in French in 1893 and released in English translation a year later in decadent hardback, accompanied by a selection of illustrations by the enormously influential Art Nouveau artist and illustrator Aubrey Beardsley. Because of the controversial subject matter — the play involves an attempt by Salomé, stepdaughter of King Herod, to seduce John the Baptist — Salome was banned in England and was not performed until the 1930s.

Magdalen College Library, Magd.Wilde-O. (SAL) 1896. Purchased through the generosity of Justin Huscher (Rhodes Scholar 1978-80) and Hilarie Huscher. Wilde, O. (1896). Salome: A Tragedy in One Act. San Francisco: The Paper Covered Book Store.

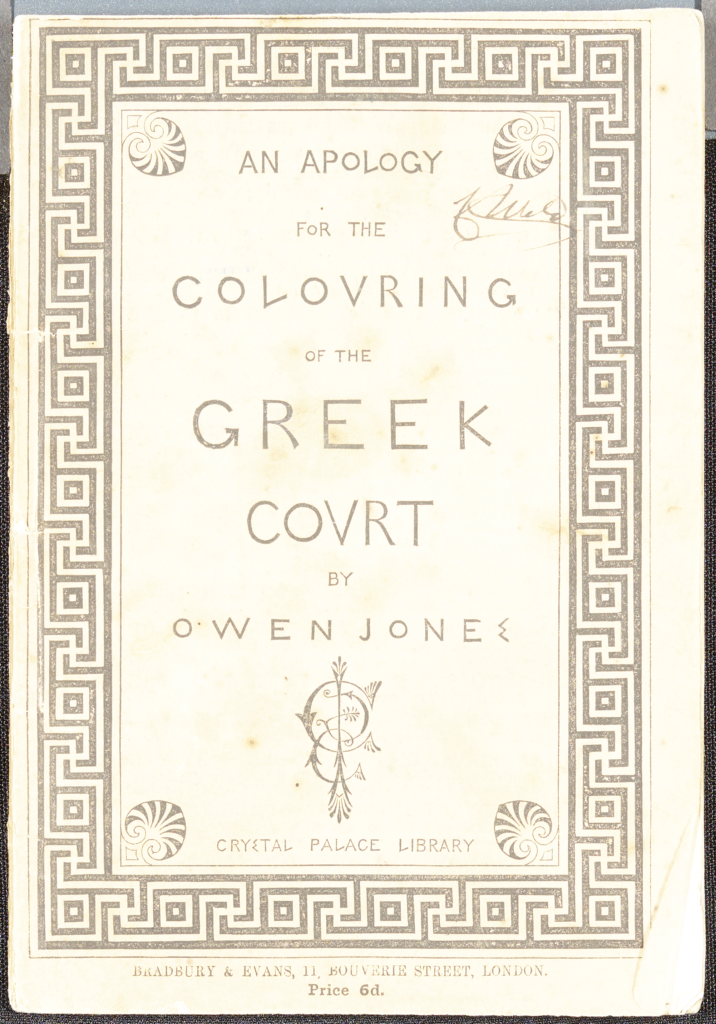

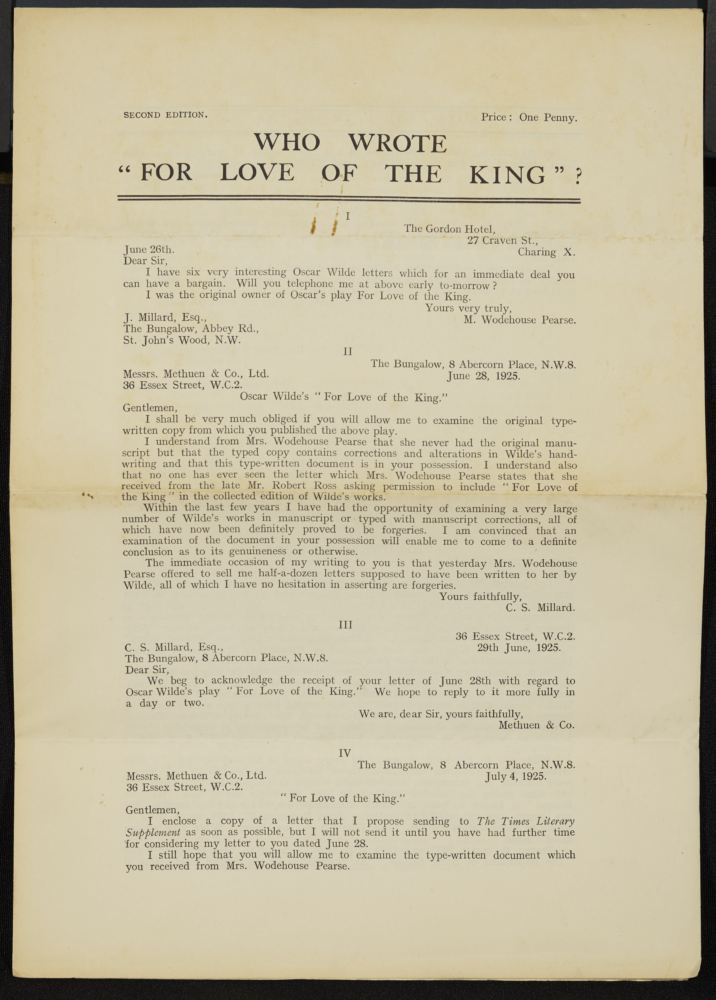

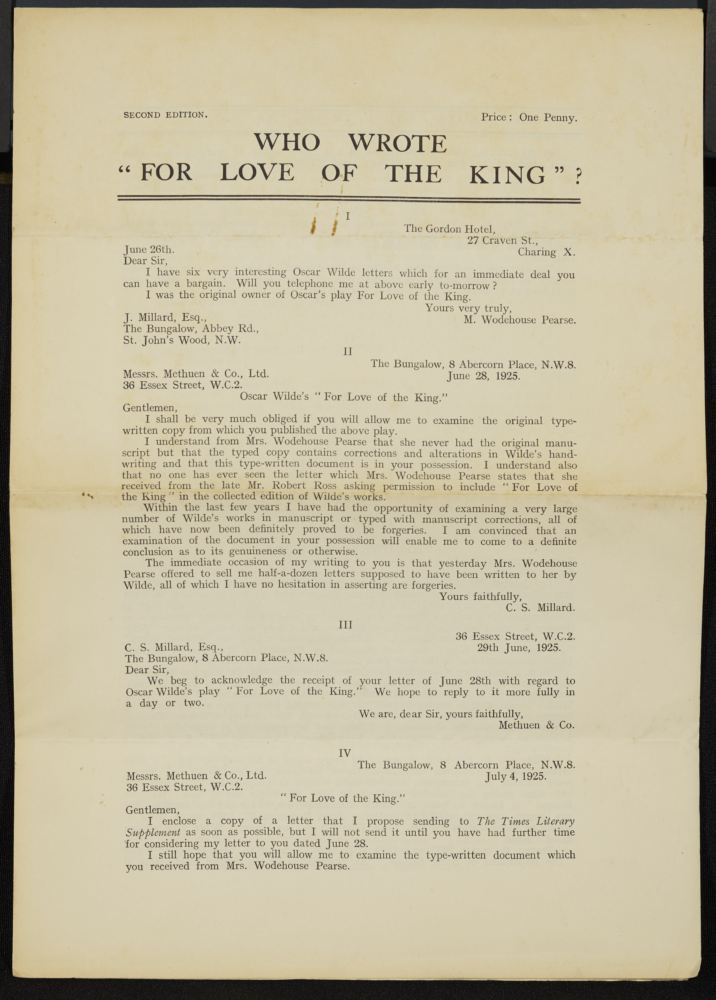

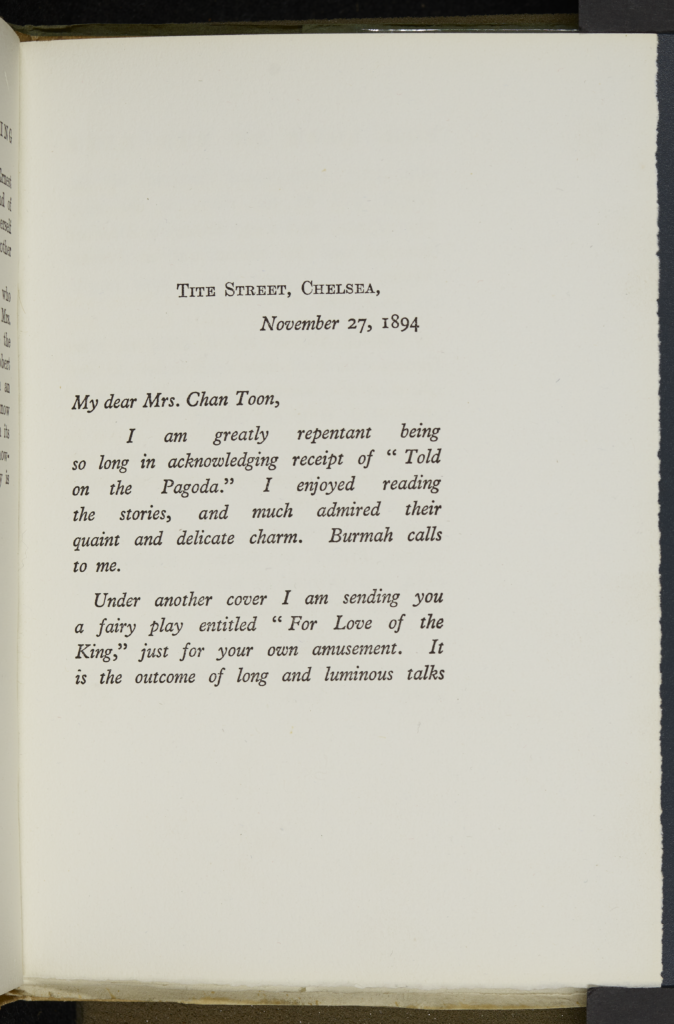

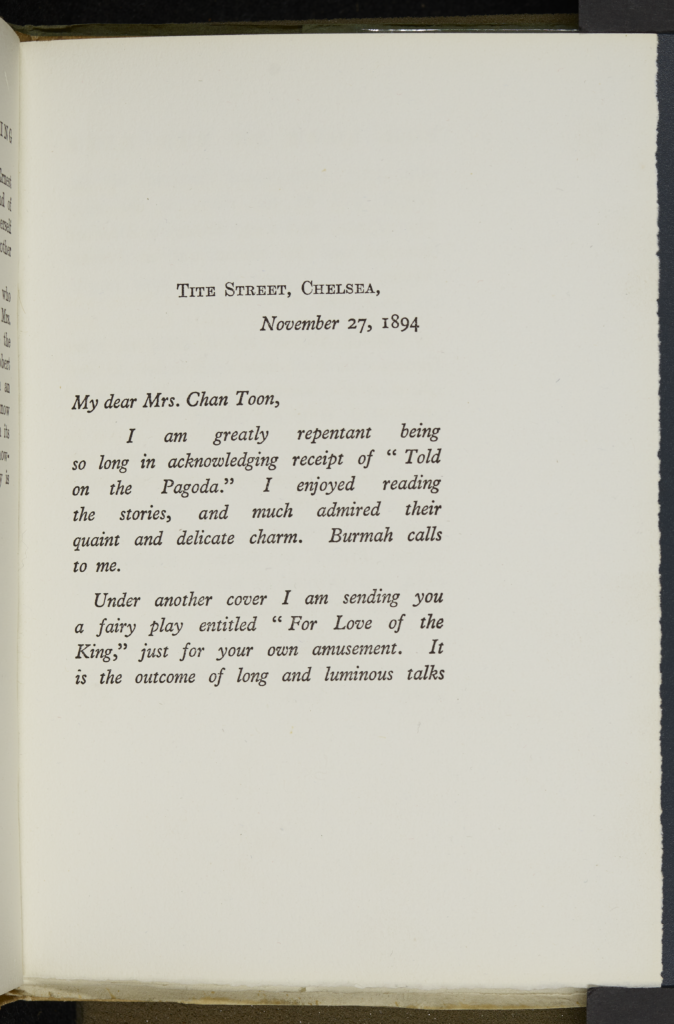

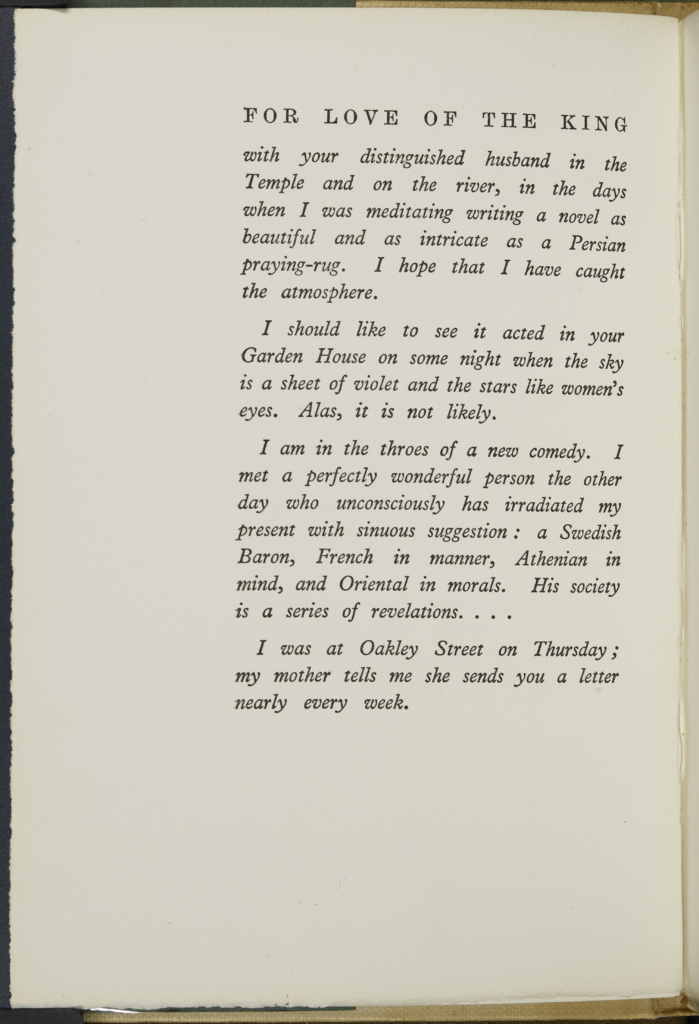

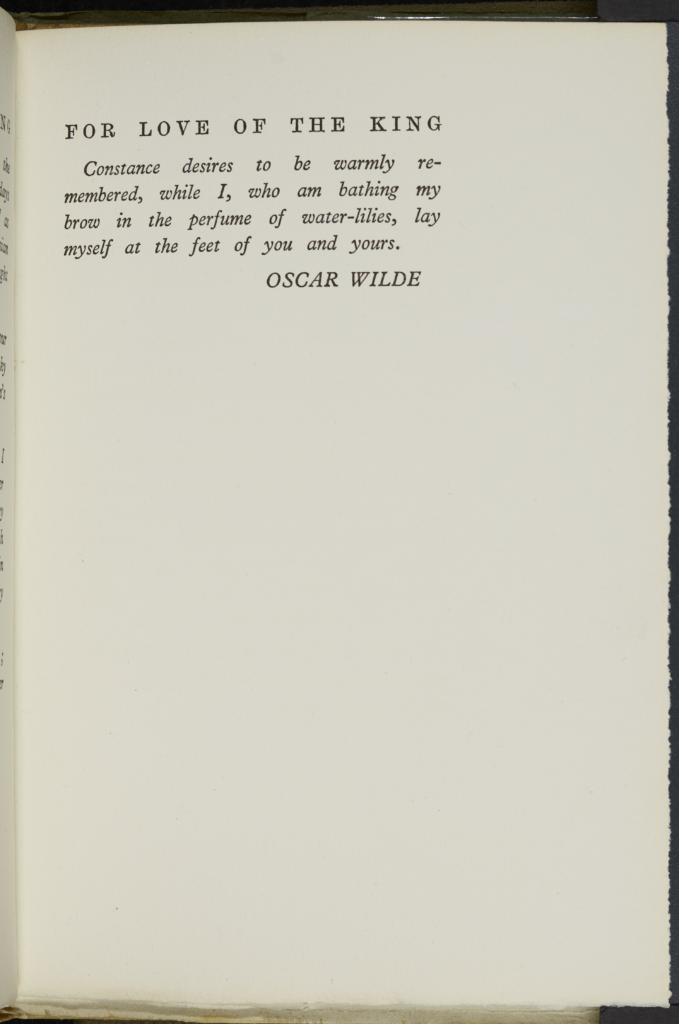

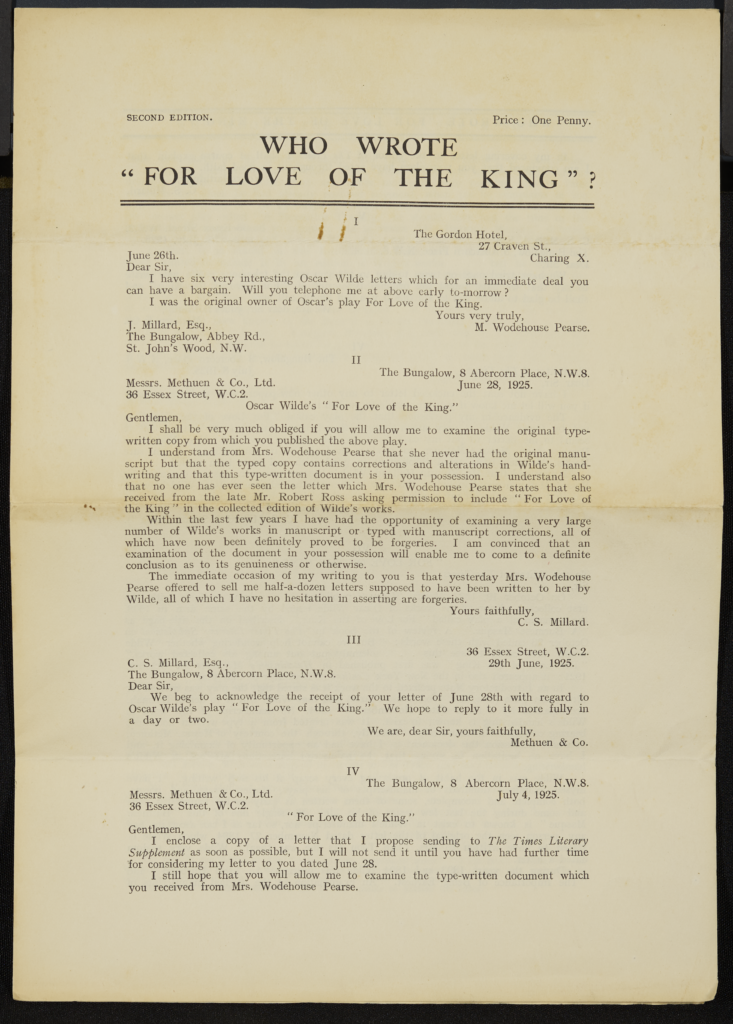

A Forgery

Originally believed to be a lost play of Wilde’s from 1894, For the Love of the King was eventually exposed as a bold forgery by Mrs Chan Toon — the married name and nom de plume of the somewhat eccentric Irish novelist Mabel Cosgrove. Cosgrove was for some time the wife of Mr Chan Toon, the nephew of a Burmese prince who practised as a barrister at Middle Temple. She spent time in Rangoon and much of her other published work appears to take inspiration from this interlude, or a reimagined version of it. The deception she carried off in the context of For the Love of the King was an elaborate one and involved a collection of forged manuscripts and letters as well as the play. Ahead of the text, she shares an invented letter between herself and Wilde, full of fancy and imagined familiarity.

Magdalen College Library, Magd.Wilde-O. (FOR) 1922. Purchased through the generosity of Justin Huscher (Rhodes Scholar 1978-80) and Hilarie Huscher. Chan Toon, Mrs. (1922). For the Love of the King. London: Methuen.

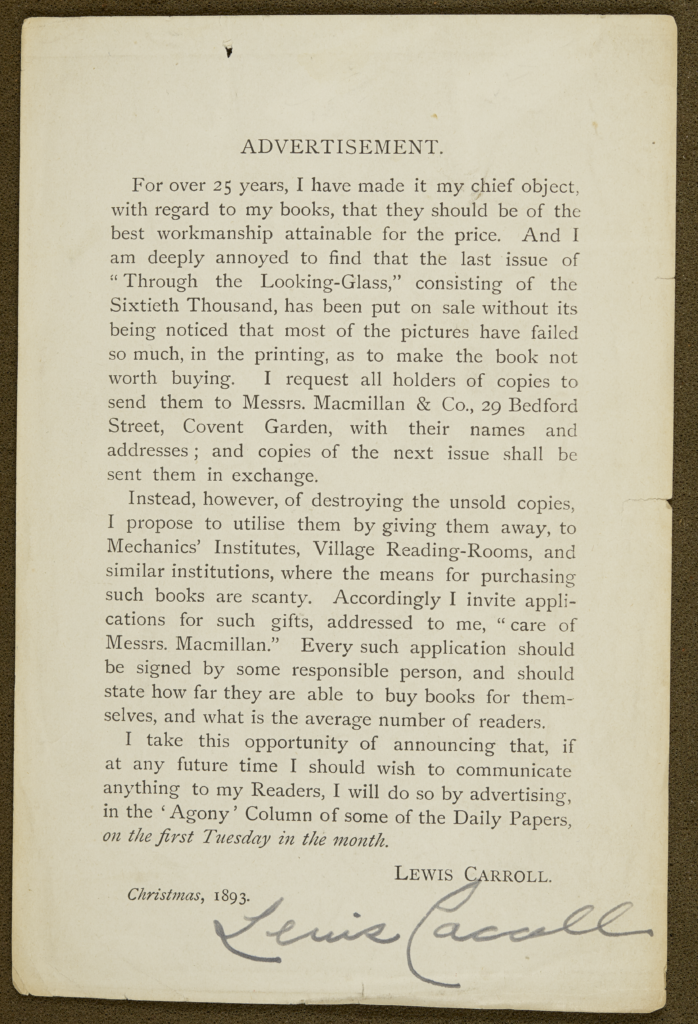

An Author’s Apology

A scarce artefact recalling copies of a recent edition of Carroll’s Through the Looking-Glass on account of the poor reproduction quality of the illustrations, signed by the author. Carroll offers readers replacements and invites applications from institutions of limited means where the second-rate copies might be appreciated, proposing to supply them free of charge. These loose leaves were tipped into books sold by Macmillan around Christmas 1893.

This item was loaned to us for the physical exhibition by the curator, Dr Alexy Karenowska. Carroll, L. (1893). An Advertisement. London: Macmillan.